The Crisis of the Old Order is the first volume of Arthur Schlesinger's Age of Roosevelt series. There are three extant volumes but Schlesinger, now 87, supposedly has been working on further volume[s] over the years/decades to cover World War II.

I bought my paperback copy new from Borders four years ago. In the meantime I’ve picked up a used copy of the third volume The Politics of Upheaval in pretty good condition at a used bookstore.

Now I need to get a copy of Volume II.

As everyone knows, The Crisis of the Old Order was made into a major science fiction blockbuster motion picture in 1977 starring Harrison Ford and Alec Guinn--- oops, wrong trilogy…

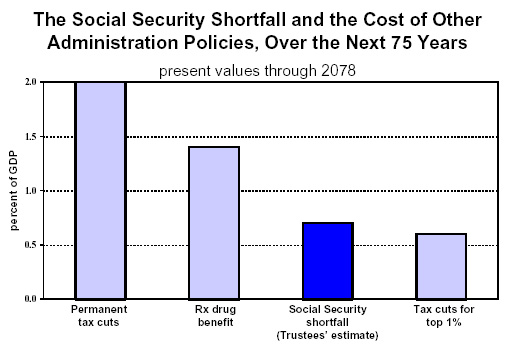

Since I've been spending some time in the last couple of months or so trying to get a handle on the Social Security issue it seemed appropriate to finally get around to reading these to get a feel for the milieu surrounding Social Security's birth. That will have to wait until later as this volume - which covers the era from 1919 to FDR's inaugural - does not provide it beyond one mention of New York State's social security initiative promulgated during his governorship.

Crisis is a combination straight-history/intellectual history/biography that actually begins at the "end" - the 1933 inaugural - before going - briefly - all the way back to the Theodore Roosevelt presidency, passing quickly over if not completely ignoring Taft and to spend more time on Wilson and the Great War. Over the first couple of hundred or so pages, Roosevelt himself often appears mainly as a side-commenter to the main events of the era not directly related to his rise. The campaign for the 1932 Democratic nomination is covered before Schlesinger finally doubles back and gives us about 70 pages of biography in time to cruise home with the summer and fall campaign and crisis of the surrounding circumstances amidst the tense and strange transition period. [So strained that it led to a constitutional amendment during Roosevelt's presidency truncating the interregnum from March to January.]

BEHOOVER MANEUVER

The emergence of Herbert Hoover as a household name for his Great War relief efforts gained him adherents on both sides of the aisle as a potential avatar/exemplar of progressive thought, the best of the modern era as signified by his engineering background as well as his managerial acumen. As he did not declare for either party prior to 1920, many Democrats, including Roosevelt, hoped he might eventually run for President on their side. He ended up as Secretary of Commerce under Harding, a tenure marked by bitter feuding with progressive Republican Secretary of Agriculture Henry C. Wallace over the fate of struggling farmers during the rural depression of the 1920s. Wallace wanted to transform the Department of Agriculture into an advocate for farmers within the federal government, Hoover considered Wallace’s embrace of protectionist legislation “fascism.” Another Secretary of Agriculture Henry Wallace would always blame his sciatica-racked father’s death in office on Hoover.

Schlesinger portrays Hoover as a tragic, obstinate, willful figure. By the end of that strained transition period following his 1932 defeat, he had gotten himself worked up to the point of believing that only his personal prescriptions could save America from the Depression and felt free to dictate terms of FDR's economic program to FDR. FDR merely termed his predecessor’s demands as "cheeky" and proceeded with the plans for the initial version of what came to be called the "New Deal."

Schlesinger's partisan approach is to basically make the case for FDR without having to making a case through argument. Example after example, anecdote after anecdote, of FDR's political skill with all of the deficiencies and inconsistencies of pleasing at least two interests at once on a particular issue showed the effectiveness of FDR's approach to political success such as his habit of saying "Yes! Yes!" to advocates of a point of view he may or may not agree with, Meaning “Yes! Yes! Keep talking” rather than “Yes! Yes! I agree!” Often leaving the latter impression whether either intentional or not. [Obviously reminiscent of another charming Presidential contender of 1990s vintage.]

LIBERAL SCHMIBERAL

The book includes a chapter on the state of American liberalism in this era and the influence of the ideas of the likes of Thorstein Veblen and John Dewey and the thrust of greater central economic planning in the wake of the success of Bernard Baruch's War Industrial Board [which Schlesinger gives short shrift to, by the way.] and the example of Russia.

Schlesinger later goes on to trace the struggles within the 1932 FDR campaign between the ["neo?"] Wilsonian "New Nationalism" outlook of embracing bigness in business and government as the inevitable outcome of modern efficiency and dealing with through greater economic and social planning vs. the Teddy Rooseveltian "New Freedom" strain of thought as exemplified by Felix Frankfurter which emphasized regulation and anti-trust.

Much of the economic thought emphasized the lack of purchasing power. Not enough of the national income was represented through wages and demand suffered [Some of that sound familiar too?]

For himself, Hoover changed his mind on what was the cause of the depression in the middle of his term. First, he thought it was domestic. Later, he thought it was international; the key was balancing the budget and shoring up the gold standard. Schlesinger implies that the reason for the change was to ward off the implications of the responsibility for lack of purchasing power on the American business community. According to Schlesinger,

In the end, Hoover, dragged despairingly along by events, decided that wherever he finally dug in constituted the limits of the permissible.FDR, who went around campaigning in the countryside by introducing himself as a farmer, for his part had a pet notion that moving city-dwellers and some of their factories back to the countryside would give them more long-term economic independence by facilitating sideline business growing and selling food and other farm commodities. By 1932, Roosevelt, who had run for vice president on the 1920 James M. Cox ticket, had more national political experience than anyone else on his campaign team. As a result, all major campaign decisions eventually filtered up to him. He was literally his own campaign manager.

Once during the campaign FDR turned his head away from the loud voice of Huey Long emanating from his phone and mentioned to someone with him that Long was one of the two most dangerous men in America.

His companions respond: And the other?

“Douglas MacArthur.”

This was in 1932.

The moment is characteristic of a book which bristles with the choice quotes, anecdotes, references and observations that you’d expect from a guy who thinks he’s Arthur Schlesinger.